First Principles for Infrastructure: Re-deriving Server, SSL & CDN Choices from the Ground Up of Business Reality

It’s 2 AM, and a founder stares at three conflicting infrastructure proposals glowing on their screen. Proposal A, from a top-tier cloud provider, paints a glorious future of serverless functions and managed microservices. Proposal B, from a veteran systems architect, argues passionately for the control and predictability of a self-managed Kubernetes cluster. Proposal C, from the internal CTO, suggests a “moderately conservative” containerized approach. Each is backed by impeccable diagrams, convincing case studies, and rigorous ROI calculations. Yet, their conclusions are worlds apart. This moment reveals a profound truth: when all advice is based on "industry best practices," the truly "best" path for you is often lost in the noise of other people's success stories.

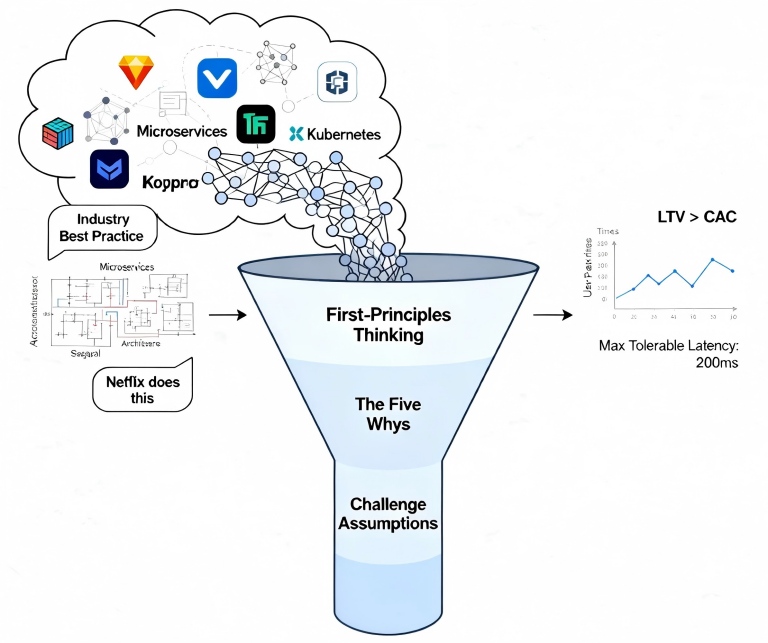

This is the most insidious trap in technical decision-making—our reliance on reasoning by analogy. We’ve forgotten how to think from first principles. Elon Musk described it as "boiling things down to the most fundamental truths and reasoning up from there." Tonight, let’s strip away all assumptions of "this is how it's done." Let's conduct a ruthless, honest deconstruction of our infrastructure choices, starting not with technology, but with the irreducible atoms of your business.

Breaking the Spell of "Reasoning by Analogy"

The most common opening line in any tech discussion is: "Netflix does it this way," "Amazon's architecture shows," or "According to Gartner...". These references have value, but they are dangerous. Analogy seeks similarity; first principles demand you confront uniqueness.

Consider this real, costly parable: A fintech startup with 50,000 daily active users, after reading JPMorgan Chase's tech blog, decided to invest millions in building a multi-active data center architecture with a blockchain settlement layer. Two years later, they burned through their funding. Their core user problem—a sluggish payment experience—remained unsolved. They had replicated "bank-grade infrastructure" but missed their own atomic truth: their users didn't care if data sync used Paxos or Raft; they cared if a payment completed in under three seconds.

The gravest danger of analogical thinking is that it uses surface-level similarities to mask fundamental differences. The unique contours of your business—your user scale, growth trajectory, fault-tolerance requirements, and compliance pressures—are the only valid coordinate system for your technology map. The next time someone persuades you with "Airbnb's microservices architecture," ask first: Is our engineering team 1/10th or 1/100th the size of theirs? Do we deploy new features weekly or quarterly?

Defining Your "Atomic Truths": The Mathematical Essence of Your Business

The starting point for first-principles reasoning is identifying those indivisible, non-negotiable Atomic Truths. These are not product requirements or user stories. They are the mathematical and logical essence of your business, stripped bare.

For an emerging video collaboration platform, Atomic Truths might be:

Truth A: 80% of user sessions involve real-time video streams; latency over 200ms causes perceived lag and frustration.

Truth B: User growth is volatile and driven by viral social shares, potentially spiking load by 1000% in hours.

Truth C: The average customer lifetime value (LTV) is $500, and the cost to serve them is $50/year in infrastructure.

Truth D: The engineering team consists of 5 full-stack developers with strong product focus but limited deep systems expertise.

These truths are cold, quantitative, and utterly unromantic. They are also the only solid ground upon which to build. From here, we begin our merciless logic.

First Principles of the Server: Computation, State, and the True Nature of Cost

The Analogical Question: "Should we use cloud VMs or bare metal?"

The First-Principles Question: "What compute, memory, and storage do we fundamentally require? How is this demand distributed over time? What premium are we willing to pay for flexibility?"

Let's perform a brutal calculation. Assume your Atomic Truths reveal:

You need an average of 64 vCPU cores for application logic.

You need 512GB of RAM, with predictable access patterns.

You need 50TB of fast storage, 40TB of which is "cold" archival data.

Traffic has a pronounced "tidal" pattern: daytime demand is 4x nighttime demand.

The Cloud's Real Cost (Reasoning Up):

On-Demand Instance Cost (Annualized):

(64 cores × $0.048/hr × 24hrs × 365 days) × Load Factor (0.4) ≈ $10,800*(The Load Factor of 0.4 accounts for not running at 100% 24/7)*

Egress Bandwidth for archival data retrieval:

(10TB active × $0.09/GB) ≈ $900Total Annual Cloud OpEx (Simplified): ~$11,700

The Bare Metal's Real Cost (Reasoning Up):

Capital Expense (CapEx) for peak-capacity server:

~$20,0003-Year Colocation & Power:

~$15,000Total 3-Year Cost: ~$35,000 | Annualized: ~$11,667

At first glance, the costs converge. But the first-principles insight is this: You are not buying servers; you are buying "the capacity to satisfy computational demand." The cloud's premium is the insurance premium you pay against uncertainty. If your growth is highly unpredictable or you need to experiment rapidly, the cloud's flexibility may be worth multiples of the price difference.

The deeper, more radical question is: Are those 64 cores fundamentally necessary? Could re-architecting a core algorithm, implementing a more efficient cache, or using a faster data structure reduce that to 45 cores? First-principles thinking forces you to challenge the demand itself before procuring the supply.

First Principles of SSL/TLS: Trust, Performance, and the Law

The Analogical Question: "Which SSL certificate should we buy? DV, OV, or EV?"

The First-Principles Question: "In what specific contexts does our business need to establish trust? How do we quantify this trust's impact on user decisions? How do different certificates balance trust signaling, cost, and performance?"

Let's dismiss all marketing about "security levels" and return to fundamental facts:

Technical Fact: DV, OV, and EV certificates offer identical cryptographic strength. They use the same algorithms to secure the data in transit.

Legal/Jurisdictional Fact: OV and EV certificates involve the Certificate Authority (CA) validating the legal entity behind the domain. This can provide differing levels of evidentiary weight in certain legal or regulatory contexts (e.g., some regions may view an EV certificate more favorably in a consumer dispute).

User Psychology Fact: In controlled studies, an EV certificate's green address bar can increase conversion rates on checkout pages by 1-3%. On a blog or marketing site, this effect is statistically zero.

Now, reason up from your Atomic Truths:

If you are a B2B SaaS company with $50,000 contracts, the legal credibility and high-trust signal of an EV certificate may justify its cost.

If you are a digital media company monetized by ads, a DV certificate is sufficient. The saved budget is better spent on content creation.

If your users are primarily on mobile devices in emerging markets, the few extra kilobytes of an EV certificate and its chain might have a more negative performance impact than its trust signal provides.

The true first-principles insight: An SSL certificate is not a "security product." It is a "trust interface." Your choice should not be based on "which is more secure" but on "where, at what cost, and to what measurable effect do we need to engineer trust?"

First Principles of the CDN: Distance, Cacheability, and the Triangle of Complexity

The Analogical Question: "Which CDN provider should we use?"

The First-Principles Question: "What percentage of our content is cacheable? What is the geographic distribution of our users? What is the measurable business impact of reducing latency by X milliseconds?"

Start with an unbreakable law of physics: the speed of light is finite. Data traveling from London to Sydney has a minimum latency of about 160ms. A CDN cannot repeal this law; it can only place content closer to the user to approach the theoretical minimum.

Reason up from your Atomic Truths:

If 95% of your users are in a single country, a regional CDN or a well-configured set of reverse proxies may be more cost-effective than a global CDN giant.

If your site is 100% dynamically generated per user (personalized dashboards, real-time data), a CDN's primary value shifts from acceleration to DDoS mitigation and edge security.

If your data shows that a 100ms latency reduction increases sign-up conversions by 2%, and the CDN cost is 0.5% of your projected revenue from those users, the investment is rational.

The most counterintuitive first-principles conclusion might be this: Sometimes, the optimal CDN strategy is to not use a CDN for certain traffic. If your core product is a real-time collaborative whiteboard (like Figma or Miro), a direct, persistent WebSocket connection between the user and your origin server may offer lower latency and greater stability than routing through a CDN's edge nodes, whose caching logic is irrelevant and whose proxy layer adds a hop.

First-Principles Synthesis: The "Irreducible Minimum Viable Stack"

After independently deriving the needs for servers, SSL, and CDN, the real challenge emerges: How do they combine into a coherent system?

Analogous thinking begins designing for "elasticity," "disaster recovery," and "multi-cloud." First-principles thinking asks: What is the simplest, irreducible combination that satisfies our Atomic Truths?

For an early-stage, data-intensive analytics startup, the derived "Minimum Viable Stack" might look shockingly simple:

Servers: A small cluster of powerful, dedicated bare-metal servers in one strategic region (compute needs are high but predictable; data gravity is a major concern).

SSL/TLS: A single wildcard OV certificate (B2B customers expect verified business identity; no need for the EV premium yet).

CDN: Used only for the documentation portal and marketing site assets (the core application is an uncacheable WebSocket/data stream).

This stack isn't "cloud-native," doesn't use service meshes, and lacks buzzwords. Its singular, defensible virtue is that it perfectly matches the Atomic Truths of this specific business at this specific stage.

As the business evolves, its Atomic Truths will change:

When user base globalizes, the CDN premise must be re-derived.

When the team scales from 5 to 50, operational complexity becomes a new primary constraint.

When the business model shifts from project-based to subscription, availability requirements may undergo a phase change.

At each inflection point, you must restart the first-principles reasoning engine—not simply bolt new components onto the old architecture.

Your First-Principles Workshop: A Four-Step Framework

This must be actionable. Here is a workshop you can run next week:

Step 1: The Atomic Truth Sprint (1 Week)

Mine the last 90 days of business data: traffic sources, session patterns, revenue per transaction, support ticket drivers.

Interview your first ten paying customers: Why did they choose you? What one thing nearly made them quit?

Audit your team's actual capabilities, not aspirational ones. How many person-hours are spent fighting fires vs. building features?

Step 2: The "Five Whys" Interrogation

For every technical assumption, ask "Why?" five times.

"We need a microservices architecture." → Why?

"Teams need to deploy independently." → Why is that important now?

"The monolith deployment is causing conflicts." → What specific conflicts? → ...

You will typically hit a fundamental Atomic Truth by the third or fourth "Why."

Step 3: Build a "Cost-Benefit-Complexity" Triaxial Model

Score every potential solution (1-10) on three axes:

Cost: Direct spend, indirect development time, ongoing maintenance burden.

Benefit: Impact on the core business metrics derived from your Atomic Truths.

Complexity: Cognitive load on the team, debugging difficulty, hiring scarcity.

Choose the option with the best balanced score, not the highest score on any single axis.

Step 4: Institute a Culture of "Falsifiable Hypotheses"

Frame every significant infrastructure decision as a testable hypothesis: "We are choosing X because we believe it will improve Y metric by Z%, based on Atomic Truth A. We will evaluate this by measuring Q over the next 90 days." When evidence disproves the hypothesis, you are intellectually obligated to change course.

When that founder finally completed their own first-principles derivation, they chose a path that shocked their advisors: They did not migrate to the cloud, nor did they build a complex container orchestration system. They dedicated the next quarter to refactoring their core data pipeline, reducing their server requirements by 40%. Then, and only then, did they re-evaluate.

Within six months, their platform handled double the traffic with 60% of the original infrastructure spend. The team reinvested the saved capital and focus into product innovation. They didn't choose an "industry best practice." They engineered their own.

The most profound gift of first-principles thinking is not a universal "right answer." It is the freedom to question everything. It liberates you from the inertia of "how it's always been done" and grants you the courage to rebuild your world from the ground up, starting with the only truths that matter: your own.

So, in your next architecture review, when the dazzling slides appear, try quietly asking the most foundational question of all: "Let's pause. Before we talk solutions, let's agree—what fundamental problem are we truly solving?" The clarity of that question will always be more valuable than the elegance of any predetermined answer.