The Insider Threat: Detecting and Mitigating the Abuse of Trust

Let's start with a scenario that might feel uncomfortably plausible. It's 2 AM, and a senior data scientist—let's call him Mark—logs into the company's cloud analytics platform from his home office. Using his fully authorized credentials, he initiates a large-scale export of the latest customer behavior models to a personal cloud storage drive he's connected. The firewall sees nothing wrong; the intrusion detection system is silent. Every packet of data is transmitted over an approved, encrypted channel. The only thing that triggers a faint, almost imperceptible alert in a secondary monitoring system is the sheer volume of data and the destination—an external storage URL that's never been associated with his account before.

Is Mark working on a groundbreaking project with a tight deadline? Or is he, in his final weeks at the company, methodically exfiltrating the intellectual property he helped build? At this moment, your traditional security infrastructure is utterly blind. The threat isn't coming from a faceless hacker in a distant country; it's coming from a trusted colleague operating from within the very walls you've spent years fortifying.

This is the paradox of the insider threat. We architect formidable defenses against external attackers, building higher walls and smarter gates, only to face a risk that already holds a key. According to Verizon's latest Data Breach Investigations Report, a staggering 30% of all data breaches involve internal actors. More sobering is the cost: the Ponemon Institute finds the average global cost of an insider-caused incident now exceeds $16.5 million. The most dangerous attack vector isn't always a zero-day exploit; it's often the abuse of legitimate, granted trust.

The Fraud Triangle: The Human Engine of an Insider Breach

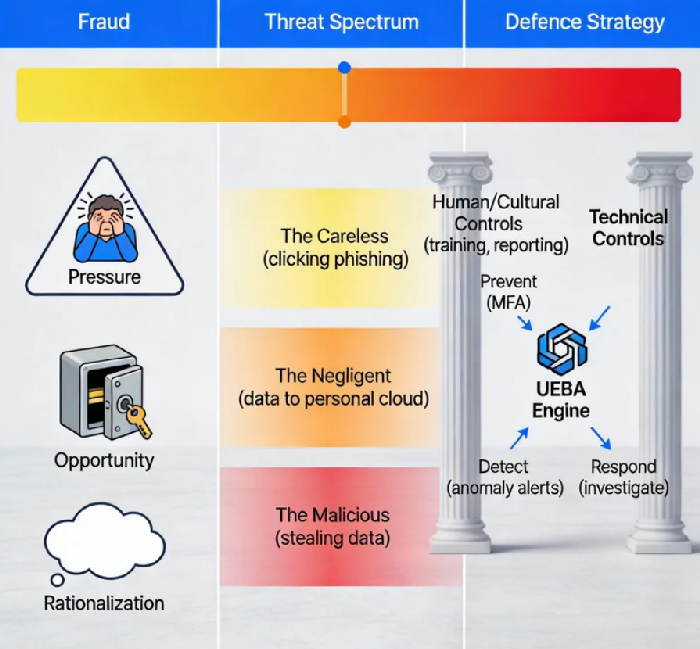

To move beyond fear and into effective strategy, we must understand the "why." Criminologist Donald Cressey's Fraud Triangle provides the most elegant framework. For an insider incident to occur, three elements must converge: Pressure, Opportunity, and Rationalization.

Pressure is the motive. It's rarely mustache-twirling villainy. It can be financial distress, a simmering grievance over a missed promotion, the stress of an impossible workload, or the anxiety of knowing one's role is being eliminated. The modern workplace—with its blurring lines between professional and personal, and the rise of remote and hybrid models—intensifies these pressures. A recent study found that nearly 45% of employees admitted to taking sensitive data when leaving a job, often rationalizing it as a "security blanket" for their next role.

Opportunity is the enabler provided by weak controls. This is where our technical and procedural defenses are tested. It manifests as excessive access rights ("Why does the marketing intern have read-access to the financial forecast folder?"), a lack of segmentation, missing activity logs, or slow offboarding processes that leave departed employees' accounts active for weeks. Opportunity whispers that the act can be carried out without getting caught.

Rationalization is the psychological loophole. This is the internal narrative that makes wrongdoing feel acceptable. "The company owes me this." "I'm just backing up my work." "No one will even notice." "Everyone else does it." This cognitive shift is what allows a normally ethical person to cross a line.

The critical insight for security leaders is this: while we can't always eliminate Pressure (personal lives are complex), and we can't control Rationalization (the human mind is a master storyteller), we have direct, absolute control over Opportunity. Our primary mission is to systematically dismantle the opportunity for trust to be abused.

The Spectrum of Risk: From Malice to Mistake

The term "insider threat" often conjures images of a malicious mole. In reality, the threat landscape is a broad spectrum, and the most common points are not malicious at all.

The Malicious Insider: This is the intentional actor—the employee stealing data for a competitor, the disgruntled sysadmin planting logic bombs, or the individual engaging in corporate espionage. They are deliberate, goal-oriented, and may use sophisticated techniques to hide their tracks, like steganography or using personal email drafts as a dead-drop.

The Careless or Compromised Insider: This is your largest and most vulnerable group. It's the engineer who pushes a database password to a public GitHub repository. It's the accountant who falls for a sophisticated phishing scam, handing over credentials that give an external attacker an "inside" foothold. Their actions are not malicious, but their negligence creates the breach. Verizon's report consistently shows that over 80% of breaches involve the use of lost or stolen credentials, many of which start with an insider's mistake.

The Third-Party Insider: Often forgotten in the perimeter model, contractors, partners, and service providers have access but may not be subject to the same security rigor or culture. Their insecure systems become your vulnerability.

Why Perimeter Defense Fails: When the Attacker is Already "Validated"

This is the core reason traditional security stumbles. Firewalls, intrusion prevention systems (IPS), and secure web gateways are designed to inspect traffic crossing a trust boundary—the line between "outside" (untrusted) and "inside" (trusted).

The insider threat obliterates this model. The malicious or compromised insider is already on the "trusted" side. Their HTTP requests to external cloud storage look like normal business traffic. Their SSH connections to internal servers are authorized. Their activities don't match signatures of known malware because they're using approved, legitimate tools—PowerShell, RDP, cloud sync clients, email—for unauthorized purposes. The castle's defenses are all facing outward, while the risk is already in the great hall.

The Shift: From Signature-Based to Behavior-Centric Security

The solution requires a fundamental pivot in mindset: from asking "Is this traffic allowed?" to asking "Is this behavior normal for this user?" This is the realm of User and Entity Behavior Analytics (UEBA) and the guiding principle of Zero Trust.

Zero Trust's mantra—"Never trust, always verify"—is the philosophical antidote to the insider threat. It assumes breach and eliminates the concept of a trusted internal network. Every access request must be authenticated, authorized, and encrypted, regardless of its origin.

UEBA is the engine that makes this practical. It uses machine learning to establish a behavioral baseline for every user and entity (servers, applications). It learns that Sarah in Finance typically logs in from New York between 8 AM and 6 PM, accesses the general ledger system, and downloads reports of <50 MB. It's a dynamic, living profile.

When behavior deviates significantly from this baseline, risk scores escalate. Key anomalies include:

Temporal and Logistical: Accessing sensitive systems at 3 AM from a foreign country.

Volume and Velocity: Downloading 10 GB of source code two days after submitting resignation.

Sequential: A series of actions that mimic an attack chain: accessing a sensitive database, connecting to a file server, compressing large amounts of data, then initiating an outbound transfer.

Peer Group Deviation: An intern exhibiting access patterns and data volumes typical of a senior architect.

Building a Proactive Defense: The Dual-Pronged Strategy

Mitigating insider risk is not solved by a single tool, but by a program that intertwines technical controls and human-centric strategies.

The Technical Prong:

Implement Strict Access Governance: Enforce the principle of least privilege (PoLP) ruthlessly. Automated access review campaigns are essential. Revoke access immediately upon role change or termination.

Deploy UEBA and Activity Monitoring: This is your core detection layer. Focus on tools that can ingest logs from all critical systems (cloud, on-prem, SaaS) to build a unified view of user activity.

Adopt a Data-Centric Approach: Use Data Loss Prevention (DLP) solutions to classify sensitive data and monitor its movement. Alert on or block attempts to exfiltrate large volumes of sensitive data to personal clouds, unencrypted USB drives, or unauthorized external emails.

Enable Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA) Everywhere: MFA is a critical control that limits the damage of stolen credentials, a common starting point for both careless and malicious insider incidents.

The Human & Cultural Prong:

Foster a Culture of Psychological Safety and Fairness: Employees who feel valued, heard, and treated justly are less likely to develop the "Pressure" and "Rationalization" corners of the Fraud Triangle. Open-door policies and regular check-ins matter.

Create Clear, Anonymous Reporting Channels: Many insider threats are first noticed by colleagues. Make it safe and easy for them to report suspicious behavior without fear of reprisal.

Deliver Continuous, Engaging Security Awareness Training: Move beyond annual checkbox compliance. Use simulations (like phishing tests) and relevant stories to teach employees to recognize risks like social engineering and the proper handling of sensitive data.

Develop a Formal Insider Risk Program: This isn't just an IT function. It involves HR, Legal, and business unit leaders. Define policies, investigation workflows, and response protocols before an incident occurs.

The journey to manage insider threat is a shift from a purely technological battleground to a human-technological ecosystem. It requires us to look beyond the firewall logs and into the more complex realms of user behavior, access patterns, and organizational culture.

The goal is not to create a dystopian panopticon of suspicion, but to build a system of intelligent, context-aware trust. In this system, normal, trusted activity flows unimpeded, while anomalous, high-risk behavior is quickly surfaced for human review. It acknowledges that trust is not a binary state granted once at hire, but a dynamic variable that must be continuously earned and verified.

Ultimately, the strongest defense against the abuse of trust is an environment where trust is both valuable and vigilantly maintained—where employees are empowered and respected, and where the systems in place are designed not to spy, but to protect the collective mission from the actions of the few, whether those actions are born of malice, mistake, or misfortune. This is the nuanced, essential work of modern security.